Birdfinding.info ⇒ Uncommon, localized, and declining. Bicknell’s Thrush is most readily found on its breeding grounds from the end of May through June. The southernmost breeding locations are Slide Mountain and Hunter Mountain in the Catskills. In the Adirondacks, accessible sites include Whiteface Mountain; in Vermont, Stratton Mountain and Mount Mansfield; in New Hampshire, Mount Washington and elsewhere in White Mountain National Forest; in Maine, Saddleback Mountain and Baxter State Park. In Quebec, accessible breeding areas include Massif-du-Sud Regional Park and Montmorency Forest. On its wintering grounds, consistent sites include at Zapotén and Cachote in the southwestern Dominican Republic.

Bicknell’s Thrush

Catharus bicknelli

Breeds in southeastern Canada and New England. Winters in the West Indies.

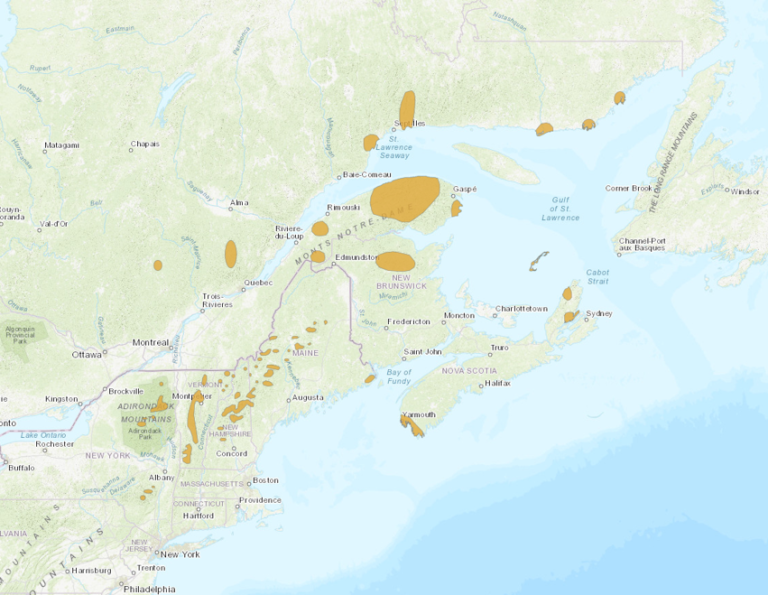

Approximate breeding range of Bicknell’s Thrush. © BirdLife International 2018

Breeding. Breeds in dense stunted coniferous forests dominated by Balsam Fir, which occur mainly near the tops of mountains and ridges from southern Quebec to New York. It also breeds in similar habitat in the early successional stages of regrowth after forest fires and other disturbances.

Bicknell’s Thrush is exceptional in having a “polygynandrous” mating system, meaning that both males and females mate with multiple partners each year so each male is attached to multiple nests and each nest has multiple males attached to it.

Its core breeding area extends from the Adirondacks of New York through the northern Appalachians to Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula. Also breeds in several scattered areas of Quebec north of the St. Lawrence, Cape Breton Island, and the Catskills of New York.

In 2010, the estimated population was in the range of 95,000 to 126,000, with about 60% breeding the U.S. and 40% in Canada.

Nonbreeding. Winters mainly in humid forests of Hispaniola, mostly but not exclusively at upper elevations. Smaller numbers winter in southeastern Cuba (the Sierra Maestra and possibly elsewhere), eastern Jamaica (the Blue Mountains), Puerto Rico, and rarely east into the Virgin Islands.

Movements. A short-distance migrant that is seldom seen on migration—much of the population may fly nonstop between breeding and wintering grounds. Northbound migration occurs mainly from mid- to late May. Birds leave the breeding grounds around the middle of September.

Identification

Generally similar to other North American Catharus thrushes, and lacking any prominent distinctive features, Bicknell’s is difficult to identify by sight.

Bicknell’s Thrush, showing gray underparts and mostly neutral-brown upperparts with subtly warmer tones on the tail and wings. (Saddleback Mountain, Maine; June 3, 2015.) © Alan Schmierer

It is essentialy identical to the Gray-cheeked Thrush, with which it was traditionally regarded as conspecific. Bicknell’s averages ~10% smaller and often shows somewhat warmer-brown plumage, especially on the tail. (For a detailed comparison, see below.)

Like its close relatives, Bicknell’s is plainly attired overall with unmarked brown upperparts and whitish underparts that have bold, blackish spots on the throat and chest. The spots extend down to the mid-breast where they become blurry.

Both Bicknell’s and Gray-cheeked differ from other Catharus thrushes in having a relatively dark, unmarked, grayish face with an indistinct eyering. Their underparts generally appear darker and grayer than the others, usually most noticeable on the flanks.

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Kaskad, Haiti; February 14, 2017.) © Jim Tietz

Bicknell’s Thrush, facial close-up. (Mount Mansfield, Vermont; May 20, 2016.) © Kent McFarland

As with other Catharus thrushes, when seen in flight its underwings show a surprisingly bold pattern of two pale bars and two dark bars.

Voice. Song is rich and musical, a series of chattering phrases that begins with a burst of whistles and ends with a lower reverberating tone. It has been rendered as “chook-chook, wee-o, wee-o, wee-o-ti-t-ter-ee.” Each rendition lasts about two seconds, and they are spaced about two to five seconds apart: Call is a slurred pe-EW! that quickly rises and falls:

Notes

Monotypic species. Formerly considered conspecific with the Gray-cheeked Thrush (minimus).

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable.

See below for comparisons of Bicknell’s Thrush with the Gray-cheeked Thrush, Hermit Thrush, and Swainson’s Thrush.

Cf. Gray-cheeked Thrush. Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s Thrushes are nearly identical and were long considered conspecific. Their breeding and wintering ranges are not known to overlap—but the population that breeds on Newfoundland, classified as Gray-cheeked, has been recognized as potentially intermediate, which suggests some history of interbreeding there. They overlap widely on migration, in May and September, as Gray-cheeked migrates throughout Bicknell’s’ range.

The internal variation within each species is enough that they overlap on all visible characteristics. Gray-cheeked is slightly larger (~10% on most measurements), but this difference is not helpful for field identification. Bicknell’s is usually a slightly warmer shade of brown overall and more likely to show a noticeably reddish-brown tail (suggesting Hermit Thrush), so some individuals can be identified as Bicknell’s on that basis.

Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s have similar songs but with different endings. Gray-cheeked usually ends with a pair of low notes—sometimes sustaining the final note, sometimes not. In contrast, Bicknell’s characteristically ends with a single, musical, richly reverberating note. When it sustains the final note, Gray-cheeked’s ending is lower-pitched and less reverberating than Bicknell’s. Their calls do not differ noticeably.

Cf. Hermit Thrush. Bicknell’s and Hermit Thrushes are similar enough to be mistaken for one another under some circumstances. Hermit Thrush is often identified by its tail coloration, which is a rusty shade of brown that usually contrasts with the rest of its upperparts. Bicknell’s’ tail also tends to appear warmer brown than the rest of its upperparts—but this effect is much less pronounced than with Hermit’s tail.

Bicknell’s also differs from the overlapping, eastern form of Hermit Thrush in having colder-brown upperparts overall and a thinner, indistinct eyering; whereas Hermit’s eyering is bold and white. Hermit’s song is much slower, consists of separate fluted notes, and lacks the reverberations of Bicknell’s. Hermit’s common calls include nasal jeers and low, percussive chuck notes.

Cf. Swainson’s Thrush. All forms of Swainson’s Thrush are usually recognizable by the buffy coloration on their faces. Swainson’s’ voice also differs notably from that of Bicknell’s: Swainson’s’ song is slower, consists mainly of separate fluted notes, then ends with a thin, high-pitched reverberation. Swainson’s’ typical call is a percussive chuck note.

More Images of Bicknell’s Thrush

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Mount Washington, New Hampshire; June 5, 2017.) © Darren Clark

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Cape May, New Jersey; May 11, 2016.) © Tom Johnson

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; November 30, 2013.) © Dax M. Román E.

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; November 30, 2013.) © Dax M. Román E.

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Monte Mégantic National Park, Quebec; July 6, 2019.) © Daniel Jauvin

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Monte Mégantic National Park, Quebec; July 6, 2019.) © Daniel Jauvin

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Mount Washington, New Hampshire; June 5, 2017.) © Darren Clark

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; December 1, 2013.) © Dax M. Román E.

Bicknell’s Thrush, singing. (Mont Miller, Murdochville, Quebec; June 4, 2018.) © Pierre Fradette

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Saddleback Mountain, Maine; May 30, 2019.) © Hugh Whelan

Bicknell’s Thrush. (Cape May, New Jersey; May 11, 2016.) © Tom Johnson

Bicknell’s Thrush, on nest. (Stratton Mountain, Vermont; July 17, 2008.) © Kent McFarland

Bicknell’s Thrush, immature. (Dixville, New Hampshire; July 23, 2014.) © Dick Dionne

Bicknell’s Thrush, immature. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; January 15, 2016.) © Rafael V. Arvelo C.

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2014. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Second Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

BirdLife International 2018. Catharus bicknelli. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22728467A132032920. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22728467A132032920.en. (Accessed August 29, 2019.)

eBird. 2022. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed July 2, 2022.)

International Bicknell’s Thrush Conservation Group. 2010. A Conservation Action Plan for Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli). Hart, J.A., C.C. Rimmer, R. Dettmers, R.M. Whittam, E.A. McKinnon, and K.P. McFarland, eds. www.bicknellsthrush.org.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Latta, S., C. Rimmer, A. Keith, J. Wiley, H. Raffaele, K. McFarland, and E. Fernandez. 2006. Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

New York Natural Heritage Program. 2019. Online Conservation Guide for Catharus bicknelli. https://guides.nynhp.org/bicknells-thrush/. (Accessed August 29, 2019.)

Raffaele, H. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.