Birdfinding.info ⇒ Most readily found on pelagic trips out of Hatteras, North Carolina, where it occurs year-round. Also locally numerous in the waters offshore from Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina. Farther north, it can often been seen in small numbers from July to October in offshore waters from Virginia to New Jersey, and more rarely to Nova Scotia. Along the southern coast of Cuba, in the vicinity of Punta Bruja, flocks can often be seen from shore.

Black-capped Petrel

Pterodroma hasitata

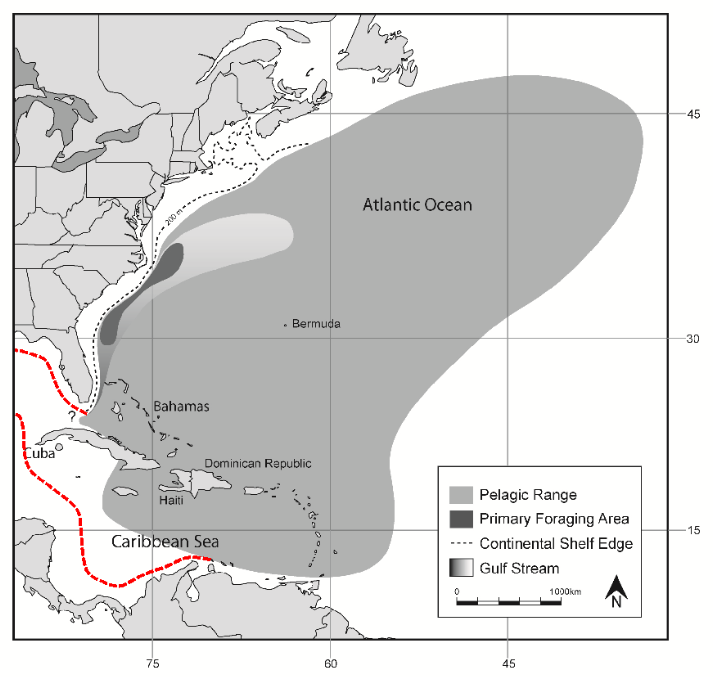

Breeds in the West Indies, mainly in southern Haiti, in smaller numbers in the Dominican Republic, and likely in southern Cuba and on Dominica. Range at sea is generally warm offshore waters of the Caribbean Sea and western North Atlantic.

Principal Black-capped Petrel breeding areas on Hispaniola. (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2018)

Breeding. Breeds from December to July (most hatch in March) in mountains of southern Haiti in the Massif de la Hotte (Pic Macaya and possibly Pic Formon) and Massif de la Selle (More La Visite and Morne Vincent). In the Dominican Republic an estimated 40 pairs nest in the western Sierra de Bahoruco (Loma del Toro), and around 2010 a colony was discovered in the Cordillera Central at Valle Nuevo National Park.

Strongly suspected to breed in the Sierra Maestra of southern Cuba, where flocks gather near the coast and are heard flying inland at night. Breeding has also been suspected in Jamaica’s John Crow Mountains.

Historically bred abundantly on Dominica and in smaller numbers on Guadeloupe and Martinique, but colonial settlers depleted those populations. There is strong evidence that it continues to breed on inaccessible mountain slopes of Dominica: a female in breeding condition was captured there in 2007 and flocks have been detected inland at night.

A 2008 estimate of the global breeding population was 1,300 to 3,100 pairs.

Nonbreeding. The core of the Black-capped Petrel’s range at sea is the Gulf Stream and adjacent waters from northern Florida to North Carolina, where it occurs year-round. There are major feeding areas off the coasts of Georgia and southern South Carolina, and off of North Carolina.

During summer and fall, small numbers follow the Gulf Stream northeast at least to Nova Scotia and likely to Newfoundland waters.

Approximate range of the Black-capped Petrel. (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2018)

Also ranges east across the Sargasso Sea, and throughout much of the Caribbean Sea west to the Cayman Islands and south to Panamanian waters, with major feeding areas along coasts of Colombia, western Venezuela, and the ABC Islands.

Outside of its core at-sea range, disperses at least occasionally into the Gulf of Mexico and east to the Azores and Madeira. Its southern limit in the Atlantic is unknown, but there are historical records from far southeast of Barbados.

Hurricanes sometimes carry Black-capped Petrels to inland locations across eastern North America. There are two records of individuals discovered dead or exhausted on the eastern coast of England, in 1850 and 1984.

Identification

Distinctive and usually easy to identify, even at long range, due its contrasty dark-and-white plumage and, in particular, its prominent white rump.

Varies significantly in certain plumage details, mainly the extent of its dark and white features. Two color morphs have been recognized—“white-faced” and “dark-faced”—but the status of the morphs is uncertain and greatly complicated by the existence of intermediate individuals (for more on this, see Frontiers of Taxonomy: Preserve the Black-capped Petrel).

Black-capped Petrel, dark-faced type. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 25, 2017.) © Tom Benson

The upperparts are mostly dark, with a black cap, white (or at least pale) nape, and large, bright white rump. A subtle “M” pattern is often discernible.

A small minority of dark-faced individuals lack the pale nape, and are therefore easily mistaken for Bermuda Petrel (see below).

Black-capped Petrel, dark-faced type. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; June 7, 2018.) © Brian Sullivan

Black-capped Petrel, intermediate, molting flight feathers. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 23, 2018.) © Peter Flood

The underparts are mostly white, usually with a conspicuous black carpal bar on the underwing, and a dark partial collar that projects down along the base of the neck, just in front of the shoulder.

Black-capped Petrel, dark-faced type. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 25, 2017.) © Tom Benson

Black-capped Petrel, white-faced type. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 23, 2018.) © Peter Flood

Black-capped Petrel, white-faced type. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; June 8, 2018.) © Steve Kelling

Black-capped Petrel, intermediate. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; June 7, 2018.) © Brian Sullivan

Black-capped Petrel, dark-faced type, lacking white nape collar and thus potentially confused with Bermuda Petrel. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 20, 2008.) © Brian Sullivan

Black-capped Petrel, white-faced type. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; June 8, 2016.) © Steve Kelling

White-faced birds typically have a small black cap bounded by a broad white nape, with extensive white on the forehead that extends back over the eyes, and an extensively white rump and tail. On the underparts, they typically show only a hint of the dark partial collar, if any, and a narrow black carpal bar.

Dark-faced birds typically have an extensive black cap with a narrow white collar (sometimes no collar), with a narrow white forehead, and a more limited white rump area. On the underparts, they typically show a distinct dark partial collar and a broad black carpal bar.

However, there are gradations in all the potentially distinguishing features of the white-faced and dark-faced types, with many intermediate individuals that are not readily assignable to either type. Some individuals seem to combine features of both types: e.g., white-faced with a broad black carpal bar.

Black-capped Petrel, white-faced type. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 20, 2008.) © Brian Sullivan

Black-capped Petrel, dark-faced type, with unusually thick partial collar and mostly dark underwings. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; June 5, 2009.) © Matt Brady

Cf. Bermuda Petrel. Black-capped and Bermuda Petrels occur together in the western North Atlantic, mainly in the Gulf Stream and adjacent waters from the vicinity of Cape Hatteras northeast to Georges Bank and east to Bermuda. In the most readily accessible portion of this zone, Black-capped is far more common and Bermuda more sought-after.

Typical representatives of the two species are readily identifiable, but plumage variability in both species complicates the identification of some individuals. The main distinctions are:

Size: Bermuda Petrel is slightly smaller than Black-capped, with a thinner, shorter bill. The bill is useful as an identifying feature mainly when it appears noticeably massive, as that rules out Bermuda Petrel.

Rump-Tail Contrast: The difference that is most conspicuous at long range under normal field conditions is in the prominence of the rump: conspicuously white on Black-capped, narrowly white on Bermuda.

Black-capped Petrel, showing typically wide white rump. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 24, 2019.) © Michael Todd

Bermuda Petrel, showing typically narrow white rump—also note dark “M” pattern. (Offshore from Bermuda; November 5, 2018.) © Derek Rogers

Black-capped Petrel, showing wide white rump contrasting with narrow black tail. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 7, 2015.) © Jay McGowan

Bermuda Petrel, showing white rump narrower than gray tail—but note weak contrast between rump and tail. (Offshore from Bermuda; November 8, 2018.) © Peter Flood

Black-capped Petrel always has a broad white rump area that usually includes the upper tail feathers (in aberrant individuals even the entire tail can be white). The dark part of the tail is usually smaller than its white rump, sometimes about the same size, but never noticeably larger.

Bermuda Petrel typically has a narrow white rump band that rarely includes any of the tail. Its uppertail is sometimes pale gray, but not bright white. On Bermuda, the dark (or pale gray, in some cases) portion of its tail is always noticeably larger than the white rump band.

Collared vs. Cowled: Bermuda Petrel has a dusky “cowl” (partial hood), whereas Black-capped has a cap bordered by a paler collar—a pale nape and cheeks—and a narrow dark partial collar projecting down from the base of the neck.

Both species vary somewhat in the extent of these features, and some individuals become ambiguous due to feather-wear.

Black-capped Petrel (left, © Skip Russell) showing a pale nape and gray partial collar, compared to Bermuda Petrel’s cowl (right, © Peter Flood).

Exceptionally, in heavily worn plumage, some Bermuda Petrels develop a partially collared appearance that resembles Black-capped.

Also exceptionally, the darkest Black cappeds may have a dark nape and extensive partial collar, but not a cowl—which is diagnostic when present.

Underwing Pattern: At a glance, Black-capped and Bermuda Petrels seem to have the same basic underwing pattern: a white center bordered by a black carpal bar and black trailing edge. However, there are subtle but diagnostic differences, as Bermuda Petrel’s underwing has a distinctive “signature” pattern of two bars (one black, one white) that rarely, if ever, appears on Black-capped.

Black-capped varies in the proportions of white and black on the underwing. White-faced birds typically have an extensively white underwing framed by a thin black carpal bar and equally thin black trailing edge.

Dark-faced birds typically have a fairly thick carpal bar and a comparably thick black trailing edge, with an equal white strip in the middle—so the net impression is of three bars: black-white-black.

Black-capped Petrel, white-faced type, showing mostly white underwing with narrow black carpal bar and narrow black trailing edge. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; June 5, 2016.) © Will Brooks

Black-capped Petrel, dark-faced type, showing underwing with broad black carpal bar and broad black trailing edge, with equal-width white area in the middle. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 31, 2020.) © Jamie Adams

Bermuda Petrel, showing most distinctive version of “signature” underwing pattern: broad black carpal bar, broad white central bar, and narrow black trailing edge. (Offshore from Bermuda; November 18, 2016.) © Tom Johnson

Bermuda Petrel, showing less distinctive version of “signature” underwing pattern: somewhat narrow black carpal bar, broad white central bar, and narrow black trailing edge. (Offshore from Bermuda; November 20, 2016.) © Tom Johnson

Bermuda’s underwing has a consistent pattern that differs from Black-capped’s. The black carpal bar is thick, covering about 30-40% of the width of the wing. In most cases (except briefly due to molt), the white area is equally thick or thicker, so the predominant pattern of its underwing is two contrasting bars—one black and the other white.

Capped vs. Masked: True to its name, Black-capped Petrel always has a dark cap, which is usually prominent, though the size of the dark area varies widely. Most Black-capped Petrels also have a pale nape, which accentuates the cap. A very small proportion of Black-capped Petrels lack the nape collar and can be mistaken for Bermuda Petrel.

On Bermuda Petrel’s head, when seen well in neutral lighting, the darkest feathering is usually around the eyes, whereas the top of its head is slightly paler, which gives it a masked (not capped) appearance. However, under normal field conditions this is often difficult to discern, and it is somewhat inconsistent: depending on molt stage and lighting, Bermuda can also appear dark-capped.

Bermuda Petrel in strong light, accentuating contrast between blackish mask and paler crown—also atypically pale underwing. (Offshore from Bermuda; November 10, 2018.) © Peter Flood

Bermuda Petrel, showing strong dark “M” pattern and white rump band narrower than dark tail. (Offshore from Bermuda; November 17, 2017.) © Peter Flood

Black-capped Petrel, atypically lacking a white nape collar and showing a subtle “M”—but note bold white rump. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 20, 2008.) © Brian Sullivan

Mantle: In both Bermuda and Black-capped, the overall coloration of the upperparts varies somewhat and changes with molt and feather-wear, as well as the persistent issue of variable lighting conditions. On average, Bermuda has paler upperparts, and it often and shows a pronounced “M” pattern. Black-capped sometimes shows an “M,” but it is subtle.

(Below are two photos of a Bermuda Petrel in worn plumage giving it a fairly strong resemblance to Black-capped Petrel.)

Bermuda Petrel, in worn plumage and showing features of Black-capped—white nape collar and dark-capped appearance—but note narrow white rump. (Offshore from Nantucket, Massachusetts; September 21, 2019.) © Benjamin Hack

Bermuda Petrel, in worn plumage and showing features of Black-capped—white nape collar and dark-capped appearance—but note bold underwing pattern. (Offshore from Nantucket, Massachusetts; September 21, 2019.) © Tim Lenz

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of two recognized subspecies—only one of which has been formally described and named. Although it has traditionally been classified as monotypic, genetic evidence and phenotypic diversity suggest that it comprises multiple populations that are distinct, divergent, and possibly eligible for recognition as separate species. (For a review that concludes against recognizing multiple species based on currently available evidence, see Frontiers of Taxonomy: Preserve the Black-capped Petrel.)

Formerly considered conspecific with Jamaican Petrel (P. caribbaea; presumed extinct), but the basis for this appears weak.

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered.

Historical Abundance and Decline. The principal cause of the Black-capped Petrel’s endangered status is not mysterious. It was intensively harvested as food throughout the colonial period.

Lee and Mackin (2008) comment wryly: “In the 1700’s Catholic bishops after serious deliberation and consultation declared that lizards and Black-capped Petrels were vegetables and thereby could be eaten during Lent. In short, the taxonomy of the species even on the Kingdom level is still not fully resolved.” In addition to clerical hypocrisy, the anecdote is a testament to the former abundance and easy exploitability of nesting Black-capped Petrels.

In the wake of intense persecution, the Black-capped Petrel was briefly believed to have gone extinct.

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2014. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Second Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

BirdLife International. 2018. Pterodroma hasitata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22698092A132624510. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22698092A132624510.en. (Accessed July 7, 2020.)

Brooke, M. 2004. Albatrosses and Petrels across the World. Oxford University Press.

eBird. 2018. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed July 25, 2020.)

Farnsworth, A. 2010. Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata), version 1.0. In Neotropical Birds Online (T.S. Schulenberg, ed.). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. https://doi.org/10.2173/nb.bkcpet.01.

Flood, B., and A. Fisher. 2013. Multimedia Identification Guide to North Atlantic Seabirds: Pterodroma Petrels. Pelagic Birds & Birding Multimedia Identification Guides, Vivlia, Hockley, Essex.

Harrison, P. 1983. Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Howell, S.N.G. 2012. Petrels, Albatrosses & Storm-Petrels of North America: A Photographic Guide. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Howell, S.N.G., and K. Zufelt. 2019. Oceanic Birds of the World. Princeton University Press.

Jodice, P.G.R., R.A. Ronconi, E. Rupp, G.E. Wallace, and Y. Satgé. 2015. First satellite tracks of the Endangered black-capped petrel. Endangered Species Research 29:23-33.

Latta, S., C. Rimmer, A. Keith, J. Wiley, H. Raffaele, K. McFarland, and E. Fernandez. 2006. Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Lee, D.S., and W.A. Mackin. 2008. Black-capped Petrel. West Indian Breeding Seabird Atlas, http://www.wicbirds.net/bcpe.html. (Accessed August 16, 2017.)

Onley, D., and P. Scofield. 2007. Albatrosses, Petrels & Shearwaters of the World. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Simons, T.R., D.S. Lee, and J.C. Haney. 2013. Diablotin (Pterodroma hasitata): a biography of the endangered black-capped petrel. Marine Ornithology 41:S3-S43.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Black-capped petrel (Pterodroma hasitata). Version 1.0. April 2018. https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/DownloadFile/156416. Atlanta.