Birdfinding.info ⇒ Endangered and declining, but still breeds in numbers on Kauai, where it is well-known for the fledglings’ attraction to outdoor lighting during September and October, which exposes them to predation and other lethal encounters. Adults arrive in late March or April and can be seen throughout the breeding season offshore and from seawatches at strategic coastal locations such as Hanapepe, Makahuena Point in Poipu, and Ninini Point in Lihue. Since the 2000s a few pairs have nested at Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge. Away from Kauai, there are no well-known consistent sites, but it seems likely that a few appear between April and October in late afternoons at strategic points along the coast of the Big Island. Seen occasionally on pelagic trips out of Kailua-Kona.

Newell’s Shearwater

Puffinus newelli

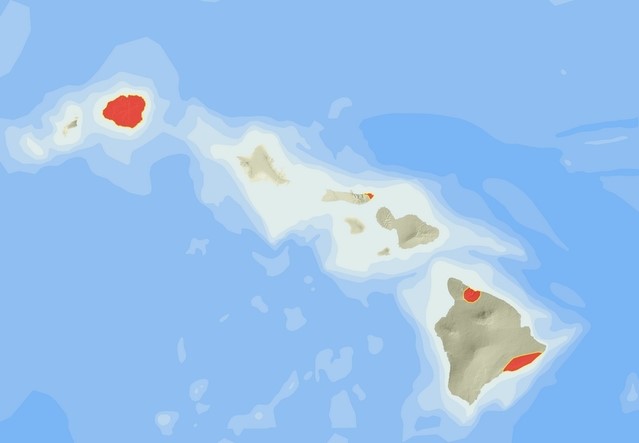

Endemic to Hawaii, where it breeds on Kauai, Lehua, Maui, and the Big Island, and possibly Molokai, Oahu, and Lanai.

Range at sea is not well understood, but appears to encompass a large portion of the Pacific Ocean. There are scattered records that span much of the tropical and subtropical Pacific: west to southern Japan and the Mariana Islands, east to southern California and Clipperton Island, and south to Australia, Fiji, and American Samoa.

Approximate breeding distribution of the Newell’s Shearwater. © Kauai Endangered Seabird Recovery Project

Breeding. Breeds from April to October in colonies on vegetated mountain slopes, usually in wooded areas, where it digs burrows among tree roots.

Most known nesting areas are on Kauai, where seven active colonies were monitored in the 2010s: five in the interior northwest and two in the east-central hills above Lihu’e. In hopes of establishing another colony, biologists have attracted a few pairs to nest at Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge. As of the mid-2010s, the Kauai population was estimated at 5,000 to 10,000 pairs.

On the Big Island, nesting colonies are known or suspected at several sites: in the Kohala Mountains, on northern slopes of Mauna Kea, and at Heiheiahulu Crater above Kalapana.

Nesting has also been confirmed, or is strongly suspected, perhaps only in small numbers, at a few other sites in the main Hawaiian Islands, including Lehua Islet (north of Ni’ihau), the mountains of eastern Molokai, and Haleakala Crater on Maui. On Oahu, surveys in 2016-2017 detected it at Mount Ka’ala and Poamoho, which suggests that it might breed there as well.

Identification

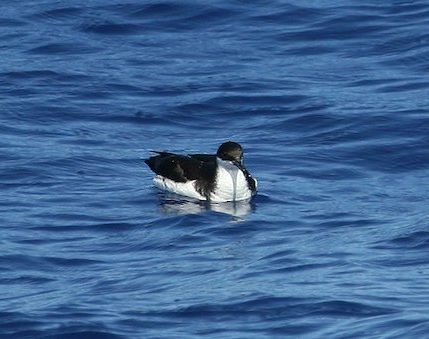

A Manx-type shearwater: medium-sized with mostly black upperparts and mostly white underparts, and notably sharp contrast between them.

Usually shows noticeable white “saddlebags” on the sides of the rump and a distinct white “gill” indentation between the black cheek and black partial collar.

The bill is mostly blackish, but often blends to bluish-gray around the base.

The legs and feet are usually grayish-pink overall, but often have extensive black patches—or in some individuals may be mostly or entirely black.

Newell’s Shearwater, showing white “saddlebags” on the sides of the rump and white “gill” indentation behind the black cheek. (Offshore from Kailua-Kona, Big Island, Hawaii; May 26, 2019.) © Jacob Drucker

Newell’s Shearwater, showing white “saddlebags” on the sides of the rump and white “gill” indentation behind the black cheek. (Kaulakahi Channel, Hawaii; April 3, 2016.) © Jacob Drucker

Newell’s Shearwater, showing white “saddlebags” on the sides of the rump and white “gill” indentation behind the black cheek. (Offshore from Kailua-Kona, Big Island, Hawaii; September 3, 2015.) © Brenda K. Rone / Cascadia Research Collective

Newell’s Shearwater, showing white “saddlebags” on the sides of the rump. (Kaulakahi Channel, Kauai, Hawaii; June 12, 2016.) © Jacob Drucker

Newell’s Shearwater, showing typically crisp contrast between black and white coloration. (Offshore from Kailua-Kona, Big Island, Hawaii; September 3, 2015.) © Daniel Webster / Cascadia Research Collective

Newell’s Shearwater, showing extensively white undertail coverts. (Northwest of Ni’ihau, Hawaii; March 27, 2020.) © Eric VanderWerf

Newell’s Shearwater, showing mostly bright-white underparts. (Northwest of Ni’ihau, Hawaii; March 27, 2020.) © Eric VanderWerf

Newell’s Shearwater. (Offshore from Nihoa, Northwest Chain, Hawaii; March 28, 2020.) © Eric VanderWerf

Newell’s Shearwater. (Offshore from Kailua-Kona, Big Island, Hawaii; September 3, 2015.) © Deron S. Verbeck / Cascadia Research Collective

Newell’s Shearwater, at rest. (Kaulakahi Channel, Kauai, Hawaii; August 27, 2007.) © Michael Walther

Newell’s Shearwater, showing mostly white underwing with isolated dark-gray mark. (Offshore from Kailua-Kona, Big Island, Hawaii; September 3, 2015.) © Daniel Webster / Cascadia Research Collective

Newell’s Shearwater, taking flight. (Offshore from Kailua-Kona, Big Island, Hawaii; September 3, 2015.) © Brenda K. Rone / Cascadia Research Collective

Newell’s Shearwater, taking flight—note irregular mix of dull-pink and dark-gray coloration of legs and feet. (Offshore from Kailua-Kona, Big Island, Hawaii; September 3, 2015.) © Deron S. Verbeck / Cascadia Research Collective

Newell’s Shearwater pair in burrow. © Kauai Endangered Seabird Recovery Project

Newell’s Shearwater, grounded—note irregular mix of dull-pink and dark-gray coloration of legs and feet. (Kauai, Hawaii; October 2007.) © Jim Denny

Voice. Calls given at nesting sites reportedly sound like a braying donkey, which inspired its native Hawaiian name, A’o (AH-OH).

Cf. Townsend’s Shearwater. Newell’s and Townsend’s Shearwaters were formerly considered conspecific and have essentially identical plumages. They are known to overlap to some extent in the waters off of western Mexico in the general vicinities of Clipperton and the Revillagigedo Islands.

The differences between them are too slight to be useful under most field conditions. Newell’s has more extensive white on its undertail coverts, and a slightly longer tail. Newell’s also shows (at least on average) somewhat sharper contrast between black and white on the neck, where Townsend’s appears grayer and blurrier.

Townsend’s breeds from January to July, whereas Newell’s breeds from April to October, so their molt timing should generally differ by about three months. Knowledge of their breeding seasons can also be useful to understanding the likelihood of encountering them near to or far from their breeding islands.

Cf. Manx Shearwater. Manx and Newell’s Shearwaters both occur in small numbers in the eastern Pacific and likely overlap to a limited extent. They were formerly considered conspecific and are very similar, but distinguishable under good viewing conditions. The most consistent differences between them are in the neck and tail.

Neck: Newell’s shows a sharper contrast between black and white on the neck, whereas Manx’s neck generally appears smudgy and grayish over a fairly large transitional area.

Tail: Newell’s is somewhat long-tailed, whereas Manx is notably short-tailed, so much that its feet often project past the end of it. Both have white undertail coverts, but when viewed from Newell’s shows a blackish area behind the white; whereas under the same conditions, Manx shows an almost all-white undertail with just a narrow black tip.

Notes

Monotypic species. At various stages of taxonomic understanding, it has been considered a subspecies of both Manx and Townsend’s Shearwaters (puffinus and auricularis).

IUCN Red List Status: Critically Endangered.

References

BirdLife International. 2019. Puffinus newelli. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T132467692A152723568. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T132467692A152723568.en. (Accessed June 22, 2020.)

eBird. 2020. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed June 22, 2020.)

Harrison, P. 1983. Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Howell, S.N.G., and K. Zufelt. 2019. Oceanic Birds of the World. Princeton University Press.

Kauai Endangered Seabirds Project. 2020. Newell’s Shearwater. https://kauaiseabirdproject.org/newells-shearwater/. (Accessed June 22, 2020.)

Pratt, H.D., P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1987. A Field Guide to the Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific. Princeton University Press.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.