Birdfinding.info ⇒ Common on its Australian wintering grounds, where it is one of the most numerous shorebirds, and during spring and fall migration periods in eastern China (e.g., Nanhui Dongtan near Shanghai), Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. In North America, it becomes fairly common along the Bering Sea coasts of Alaska in late August and September, and rare but regular in south-coastal Alaska. Farther south, there are several sites where it is seen nearly annually at some point between mid-September and early November. These include: in British Columbia, Iona Island, Reifel Bird Sanctuary, and Boundary Bay; in Washington, Ocean Shores; in Oregon, Fern Ridge Lake; and in Hawaii, James Campbell and Pearl Harbor National Wildlife Refuges on Oahu, and Kealia Pond National Wildlife Refuge on Maui.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper

Calidris acuminata

Breeds in northeastern Siberia. Winters in Australasia.

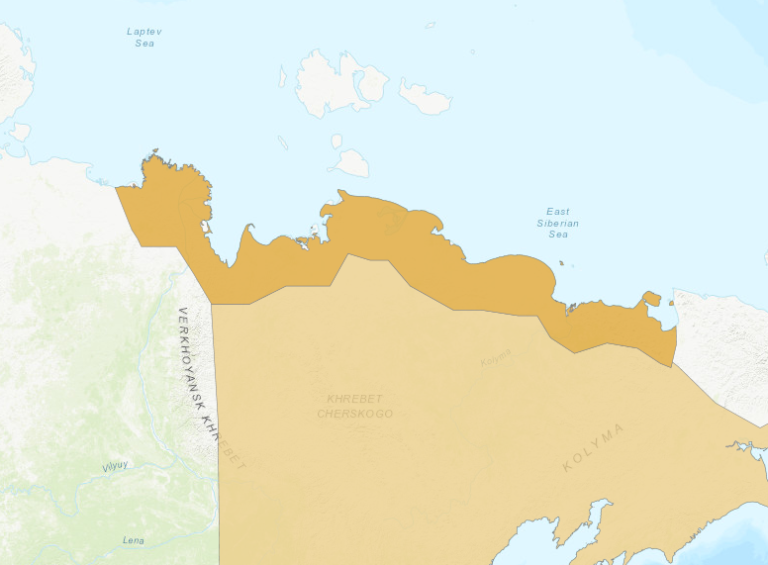

Approximate breeding range of the Sharp-tailed Sandpiper (in dark orange). © BirdLife International 2016

Breeding. Breeds from late May to July on arctic tundra on the coastal plain of Siberia from the Lena River Delta east to Chaunskaya Bay.

Nonbreeding. Winters in various types of wetlands, both fresh and coastal, mostly in areas with a muddy substrate and grassy margins.

Most of the population apparently winters in Australia—throughout the continent wherever there is suitable wetland habitat. Significant numbers also winter on Timor, New Guinea, Tasmania, New Zealand, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu. Smaller numbers winter regularly west to Bali and north to the Philippines, Taiwan, and the Marshall Islands, and rarely west to Thailand and east into Polynesia.

Movements. Northbound migrants begin leaving Australia in March and spend several weeks in subtropical and temperate East Asia, including Korea and Japan, before proceeding inland across Mongolia and eastern Russia. They arrive on their breeding grounds from late May into early June.

After breeding, adults return south along the same route from July to September.

Most juveniles migrate separately, departing the breeding grounds in August and arriving on the wintering grounds in November. Large numbers of juveniles wander east to Alaska, and small numbers continue south along the western coast of North America. Many fly south across the Pacific, and large flocks sometimes layover in the Northwest Chain of the Hawaiian Islands.

Vagrants have occurred nearly worldwide, especially from September into November, when the juveniles are highly mobile. There are records from throughout North America, northern and western Europe (mainly Scandinavia and the British Isles), and southern Asia, with a scattering of records from South America, Africa, and various oceanic islands, including Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic.

Identification

A medium-sized calidrid with a short, slightly decurved bill and yellowish legs. Often shows rusty, buffy, and orange tones, but many individuals lack these tones. Easily confused with Pectoral Sandpiper, which occurs throughout its range (Cf. Pectoral Sandpiper below), and potentially confusable with several other related species.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, breeding plumage. (Nanhui Dongtan, Shanghai, China; May 5, 2018.) © Charles Wu

The legs are typically some shade of yellow, usually dull and often tinged greenish—sometimes grayish.

In all plumages, the crown is mostly brown or rufous, with fine dark spots or streaks. Typically shows at least a vaguely defined pale eyebrow below the crown, and often shows a vaguely defined, broad, brownish stripe across the face.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, breeding plumage—note chestnut crown and greenish legs. (Lena Delta, Sakha Republic, Russia; June 30, 2017.) © Andrew Spencer

Breeding adults are marked with small dark chevrons on the underparts. In peak breeding plumage, the markings can appear throughout the underparts, but many breeding adults are more sparsely marked below.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, entering breeding plumage, showing sparse chevron markings on the belly. (Tolderol, South Australia; April 14, 2019.) © Kym Nicolson

The upperparts and chest of breeding adults in fresh plumage are typically infused with rusty and buffy tones—but this varies widely as some individuals are bright and orangey whereas some are much duller. These tones fade to gray-brown during the summer.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, entering breeding plumage, showing sparse chevron markings on the belly. (Xincheng, Taiwan; March 22, 2018.) © David Beadle

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, in very faded, plain-brown breeding plumage. (Swan Creek Wetlands, Baltimore, Maryland; September 1, 2017.) © Linda Chittum

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, in faded, plain-brown breeding plumage. (Bangholme, Victoria, Australia; September 22, 2019.) © Ricardo Simao

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, breeding plumage. (Taean, South Korea; May 18, 2003.) © Kim Hyun-tae

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, breeding plumage. (Nanhui Dongtan, Shanghai, China; May 8, 2018.) © Kai Pflug

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, breeding plumage. (Piute Ponds, Los Angeles, California; May 29, 2019.) © Mark Scheel

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, breeding plumage, showing diffuse chevron markings throughout the breast. (Middleton Island, Alaska; August 31, 2012.) © Charlie Wright

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, breeding plumage. (Lake Ellesmere, Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand; February 20, 2014.) © Steve Attwood

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, breeding plumage. (Geoff Skinner Reserve, Wellington Point, Queensland, Australia; March 17, 2018.) © Terence Alexander

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, in faded, plain breeding plumage. (Jawbone Flora and Fauna Reserve, Hobsons Bay, Victoria, Australia; September 27, 2017.) © David Adam

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, molting out of breeding plumage, showing sparse chevron markings on the belly. (Flat Rock, Ballina, New South Wales, Australia; September 12, 2016.) © Steven McBride

Nonbreeding adults are mostly plain, spotted gray-brown above and variably marked with a few dark chevrons below.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, nonbreeding plumage, showing warm-brown crown, pale brow, and darker cheek—note chevrons on flanks. (Cairns, Queensland, Australia; September 18, 2011.) © Ryan Shaw

Nonbreeders are both nondescript and variable, not particularly distinctive, and easily confused with several related species. Among the most consistent and distinctive features is the crown, which is streaked but often shows a warm shade of brown.

Some nonbreeders show a notably pale face—but this pattern varies, and most instead show a pale brow and darker stripe from the lore to the cheek.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, nonbreeding plumage, showing warm-brown crown and pale face. (Iona Dwyer Oval Lagoons, Wynnum West, Queensland, Australia; December 14, 2019.) © Terence Alexander

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a pale example of nonbreeding plumage. (Thorneside, Redland, Queensland, Australia; January 11, 2019.) © QuestaGame

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a pale example of nonbreeding plumage. (Geoff Skinner Reserve, Wellington Point, Queensland, Australia; March 3, 2018.) © Terence Alexander

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, in a warm-brown example of nonbreeding plumage. (Laverton Creek Mouth, Hobsons Bay, Victoria, Australia; October 17, 2014.) © Andrew Allen

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, nonbreeding plumage, showing warm-brown crown and pale face. (Connewarre, Victoria, Australia; December 21, 2019.) © David Tytherleigh

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, nonbreeding plumage, showing sparse chevron markings on the underparts. (Hexham Swamp Nature Reserve, Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia; December 24, 2018.) © Roksana and Terry

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, nonbreeding plumage, showing chestnut crown with dark streaks. (Ash Island, Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia; December 24, 2018.) © Roksana and Terry

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a pale and nondescript example of nonbreeding plumage. (Port of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; December 30, 2018.) © Tyde Bands

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a pale, drab example of nonbreeding plumage. (Wynnum West, Queensland, Australia; February 17, 2019.) © Hayley Alexander

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a pale, sandy example of nonbreeding plumage. (Lake Borrie, Point Wilson, Victoria, Australia; December 2, 2019.) © Paul Fenwick

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a warm-brown example of nonbreeding plumage. (Laverton Creek Mouth, Hobsons Bay, Victoria, Australia; October 4, 2018.) © Andrew Allen

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a dull-brownish example of nonbreeding plumage. (Lake Ellesmere, Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand; February 20, 2014.) © Steve Attwood

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a contrasty example of nonbreeding plumage—note streaked, chestnut crown. (Queens Esplanade, Thorneside, Redland, Queensland, Australia; October 3, 2019.) © Michael Daley

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a plain-gray example of nonbreeding plumage. (Lake Ellesmere, Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand; November 24, 2012.) © Steve Attwood

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a sandy-brown example of nonbreeding plumage. (Lake Borrie, Point Wilson, Victoria, Australia; December 2, 2019.) © Paul Fenwick

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a plain-gray example of nonbreeding plumage. (Kedron Brook Wetlands Reserve, Northgate, Queensland, Australia; February 10, 2018.) © Terence Alexander

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, an especially plain-gray example of nonbreeding plumage. (Kedron Brook Wetlands Reserve, Northgate, Queensland, Australia; February 10, 2018.) © Terence Alexander

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, nonbreeding plumage, showing almost uniformly dark upperparts and contrastingly pale face. (Iona Dwyer Oval Lagoons, Wynnum West, Queensland, Australia; December 14, 2019.) © Terence Alexander

Juveniles typically have bright rufous and buffy, sometimes orange, tones throughout much of their plumage, especially on the upperparts and chest. But their coloration varies widely—from pale and dull to mostly orange.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile in typical plumage. (St. Paul Island, Alaska; August 27, 2016.) © Paul Budde

The juvenile’s crown is rich chestnut with dark streaks, and contrasts with a broad whitish eyebrow—resembling the adult’s pattern but richer in color and contrast.

Unlike the adults’ chevron markings, juveniles have thin streaks on the chest.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile in typical fresh plumage. (St. Paul Island, Alaska; September 5, 2018.) © Luke Seitz

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with extraordinarily orange plumage. (St. Paul Island, Alaska; August 30, 2012.) © Ryan O’Donnell

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with rich orange-buffy plumage and unusually dark chest. (Serangan Island, Bali, Indonesia; October 26, 2014.) © Rusman Budi Prasetyo

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with unusually uneven plumage: dark chestnut crown, contrasty upperparts, and buffy chest. (Geoff Skinner Reserve, Wellington Point, Queensland, Australia; October 14, 2018.) © Michael Daley

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile in typical plumage. (Geoff Skinner Reserve, Wellington Point, Queensland, Australia; November 2, 2018.) © Michael Daley

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile in fresh plumage. (Teslin Lake, Yukon Territory; September 8, 2016.) © Teslin Lake Bird Observatory

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile showing typically buffy breast and chestnut crown. (Honouliuli Unit, Pearl Harbor National Wildlife Refuge, Oahu, Hawaii; October 27, 2018.) © Sharif Uddin

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with orange-buffy underparts and rusty upperparts. (Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; September 5, 2019.) © Luke Seitz

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with generally buffy plumage. (Muskegon County Wastewater Management System, Muskegon, Michigan; October 5, 2019.) © Brendan Klick

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile showing buffy chest. (Iona Island, British Columbia; November 3, 2019.) © Blair Dudeck

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile showing pale pinkish-buffy wash on the chest. (Western Treatment Plant, Cocoroc, Victoria, Australia; October 21, 2017.) © John Cantwell

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile, showing strong contrast between chestnut crown and whitish face. (James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge, Oahu, Hawaii; November 18, 2016.) © Sharif Uddin

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile showing generally buffy plumage with rusty highlights. (Longford, Victoria, Australia; November 4, 2018.) © Roni Greer

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with unusually uneven plumage: dark chestnut crown and mostly whitish feather edges. (Geoff Skinner Reserve, Wellington Point, Queensland, Australia; October 14, 2018.) © Michael Daley

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with unusually pale, contrasty plumage. (Whiffin Spit Park, Sooke, British Columbia; October 21, 2018.) © Kim Beardmore

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with plain buffy plumage. (Kianawah Road Wetland, Hemmant, Queensland, Australia; November 24, 2019.) © Terence Alexander

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with unusually pale plumage. (Whiffin Spit Park, Sooke, British Columbia; October 21, 2018.) © Kim Beardmore

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile. (Western Treatment Plant, Cocoroc, Victoria, Australia; October 29, 2018.) © Andrew Allen

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with pale-buffy plumage. (Honouliuli Unit, Pearl Harbor National Wildlife Refuge, Oahu, Hawaii; October 6, 2017.) © Eric VanderWerf

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with atypically pale-buffy plumage. (Kirk Point, Point Wilson, Victoria, Australia; November 6, 2016.) © Mark Broomhall

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with unusually dull plumage. (Iona Island, British Columbia; November 3, 2019.) © Blair Dudeck

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with unusually dull plumage. (Geoff Skinner Reserve, Wellington Point, Queensland, Australia; November 3, 2018.) © Hayley Alexander

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with unusually pale-gray plumage—but note contrastingly rusty crown. (Coorong National Park, South Australia; December 30, 2018.) © Nik Mulconray

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with unusually cold gray-and-blackish plumage—but note contrastingly rusty crown. (Tolderol Game Reserve, Alexandrina, South Australia; November 6, 2017.) © Kym Nicolson

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with subtle buffy plumage. (Kianawah Road Wetland, Hemmant, Queensland, Australia; November 24, 2019.) © Terence Alexander

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with dull plumage. (Lake Ellesmere, Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand; November 10, 2012.) © Steve Attwood

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile in crisp, bright plumage. (Westmorland, California; October 11, 2019.) © John Harris

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile showing chestnut crown. (Muskegon County Wastewater Management System, Muskegon, Michigan; October 6, 2019.) © Geoff Malosh

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile. (Robert Findlay Wildlife Reserve, Miranda, North Island, New Zealand; November 17, 2018.) © Lars Petersson

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with unusually pale plumage. (Muskegon County Wastewater Management System, Muskegon, Michigan; October 6, 2019.) © Geoff Malosh

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with bright, contrasty plumage. (Eastlakes Golf Course, Botany Bay, New South Wales, Australia; October 24, 2019.) © Richard Murray

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with bright plumage. (Boundary Bay, British Columbia; September 4, 2014.) © Liron Gertsman

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile. (Coorong National Park, South Australia; December 30, 2018.) © Nik Mulconray

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile in strong light. (Nathan Road Wetlands Reserve, Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia; November 3, 2019.) © Michael Daley

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile in crisp plumage. (Point Wilson, Victoria, Australia; October 22, 2018.) © Andrew Allen

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, juvenile with bright orange-buffy upperparts. (Reifel Bird Sanctuary, British Columbia; October 5, 2010.) © Ilya Povalyaev

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, showing mostly pale underwing. (Kurnell, Sutherland Shire, New South Wales, Australia; January 22, 2020.) © J.J. Harrison

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper in flight, showing drab upperwing and divided rump. (Cairns, Queensland, Australia; October 31, 2018.) © James Bailey

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, trailing mud during takeoff. (Pouhala Marsh, Oahu, Hawaii; November 30, 2019.) © Eric VanderWerf

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, male displaying to female—long before the breeding season and far from the breeding grounds. (Tamar Island Wetlands, West Tamar, Tasmania, Australia; January 15, 2019.) © Helen Cunningham

Cf. Pectoral Sandpiper. Pectoral and Sharp-tailed Sandpipers overlap widely in eastern Asia and around much of the Pacific, and can occur together nearly worldwide. Sharp-tailed’s breeding range is encompassed within Pectoral’s and, although they winter in broadly separate areas (Australia and South America), juveniles of the two species often flock together and apparently end up wandering into one another’s migratory ranges as a result.

Breeding adults are easily distinguished, but nonbreeding adults and juveniles can be very similar and actually overlap in most features. Male Pectoral is about 10-15% larger than Sharp-tailed in every dimension, but females are much closer, and the size distinction is rarely useful without a direct comparison.

To distinguish the two species in their similar plumages, the first step is to determine whether the bird in question is a juvenile or an adult, because the differences between the species differ by age-class. (Note that around December, the juvenile plumages transition into some version of a nonbreeding adult plumage, when some identifications can be more complicated.)

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a plain-plumaged juvenile—similar to Pectoral. (Honouliuli Unit, Pearl Harbor National Wildlife Refuge, Oahu, Hawaii; October 10, 2017.) © Eric VanderWerf

Pectoral Sandpiper, a bright-plumaged juvenile—similar to Sharp-tailed. (Philomath Sewage Ponds, Philomath, Oregon; September 20, 2017.) © Nels Nelson

Juveniles: Overall, juvenile Pectoral and Sharp-tailed Sandpipers resemble one another more closely than they resemble the adults. In both, juveniles are rustier and buffier than adults, especially on the crown, back, wings, and chest, and they lack the adults’ distinct patterns of markings on the underparts. Instead, juveniles typically have indistinct markings, mostly on the chest but also on the sides and flanks. Most also have a buffy wash on the chest that varies in brightness and extent.

On average, Sharp-tailed juveniles are warmer- and brighter-colored than Pectoral, but there is wide variation within each species and they overlap broadly. The brightest juvenile Pectorals are much brighter than a dull juvenile Sharp-tailed, so they are very easily confused.

For juveniles with ambiguous coloration, the pattern on the chest is usually diagnostic—although juveniles of both species have less heavily marked underparts than adults, juvenile Pectoral usually shows the same basic chest-marked pattern as an adult Pectoral, whereas juvenile Sharp-tailed usually has a buffy chest with only a few marks on the sides.

For the identification of adult Pectoral and Sharp-tailed Sandpipers, key distinctions include:

Chest Demarcation: Adult Pectoral Sandpipers, both breeding and nonbreeding, have a densely streaked throat and chest, and a white lower breast and belly. The demarcation between the marked and unmarked portions of the underparts is crisp.

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper rarely, if ever, shows a crisp demarcation between marked and unmarked areas. Instead, it tends to have denser, bolder markings on the chest and sparser, weaker markings on the lower breast and belly, with a gradual transition between them. The location of the transition varies, and in some cases Sharp-tailed can resemble the pattern on Pectoral.

Shape of Markings on Underparts: In general, Sharp-tailed Sandpiper’s underparts are marked with V’s or chevrons, whereas Pectoral’s underparts are marked with streaks (or sometimes dots or blurs).

Presence of Markings on Flanks: Almost all adult Sharp-tailed Sandpipers have markings along the sides, flanks, and undertail coverts. A few pale nonbreeding adults, are nearly all-white below, but these are exceptional and typically also have unmarked chests, so they do not resemble Pectorals.

Bill Color: Both Pectoral and Sharp-tailed’s bills tend to be dark, blackish toward the tip and noticeably paler at the base. When seen clearly, Pectoral tends to show some yellow at the base, whereas Sharp-tailed usually appears grayish or greenish at the base (or all-dark). This feature is not reliable for positive identification of Sharp-tailed, but it appears to be reliable for some Pectorals—if there is yellow at the base of the bill, it is almost certainly Pectoral.

Pectoral Sandpiper, nonbreeding adult with warm, buffy-brown coloration and indistinct streaking on the chest—thus similar to Sharp-tailed. (East Meadows, Northampton, New Hampshire; October 2, 2010.) © Ian Davies

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, a plain-gray nonbreeding adult showing indistinct spots or streaks on the chest—similar to Pectoral. (Kedron Brook Wetlands Reserve, Northgate, Queensland, Australia; February 10, 2018.) © Terence Alexander

Leg Color: Because of variation within both species, leg color is not diagnostic, but Pectoral tends to show yellower legs than Sharp-tailed. Both species can have bright yellow legs, but Pectoral’s are consistently yellow or orange whereas Sharp-tailed’s tend to be duller and greener. This distinction applies more consistently to nonbreeding adults than to other plumages.

Cf. Long-toed Stint. Sharp-tailed Sandpiper’s color and pattern are remarkably similar to those of the smaller Long-toed Stint. This is especially true of juveniles but also applies to nonbreeding and some breeding adults as well. In general, the two species can be distinguished by size—as there is no overlap in any of their measurements—but the smallest Sharp-tailed measures only about 10-15% longer than the Long-toed Stint, so some individuals may require a close study to identify.

Notes

Monotypic species.

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2014. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Second Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

BirdLife International. 2016. Calidris acuminata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22693414A93405394. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693414A93405394.en. (Accessed July 19, 2020.)

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press.

eBird. 2020. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed July 21, 2020.)

Hayman, P., J. Marchant, and T. Prater. 1986. Shorebirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Mullarney, K., L. Svensson, D. Zetterström, and P.J. Grant. 1999. Birds of Europe. Princeton University Press.

Pratt, H.D., P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1987. A Field Guide to the Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific. Princeton University Press.

Pratt, H.D. 1993. Enjoying Birds in Hawaii: A Birdfinding Guide to the Fiftieth State (Second Edition). Mutual Publishing, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Robson, C. 2002. Birds of Thailand. Princeton University Press.

Sibley, D.A. 2000. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Xeno-Canto. 2020. Sharp-tailed Sandpiper – Calidris acuminata. https://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Calidris-acuminata. (Accessed July 19, 2020.)