Birdfinding.info ⇒ Locally common in its limited range. The most accessible site for this species in the D.R. is the upper section of Zapotén Road. It can also be found at Los Arroyos, and sometimes at upper elevations of Alcoa Road. In Haiti, it is readily found in upper elevation forests in the Massif de la Hotte’s Pic Macaya Biosphere Reserve and in and around La Visite National Park.

Western Chat-Tanager

Calyptophilus tertius

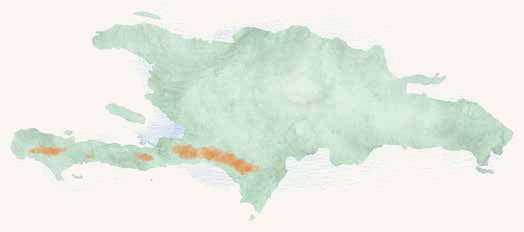

Endemic to the mountains of southwestern Hispaniola.

Mainly in humid montane forests of the Tiburon Peninsula, in the Massif de la Hotte, Massif de la Selle, and in the adjacent Sierra de Bahoruco of the southwestern Dominican Republic.

The subspecies abbotti formerly lived in the dry thorn forest of Gonâve Island, but has not been reported in recent years and may be extinct.

Identification

A robust, thrush-sized bird that is dark brown above and grayish below, with brownish flanks and a bright white throat.

Forages in the understory and on the ground, usually in pairs. Its behavior resembles certain antshrikes and foliage-gleaners.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; May 17, 2016.) © Kenny Diaz

The orbital skin is gray, which differentiates it from Eastern Chat-Tanager, but both species have a small yellow crescent in front of the eye—this is often concealed and becomes most visible during displays.

Western Chat-Tanager, showing faint yellow crescent on lore. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic; August 3, 2012.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; June 1, 2015.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; April 27, 2011.) © Rafael V. Arvelo C.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic; April 15, 2018.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager—the orbital skin sometimes appears pale, but not yellow. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic; May 17, 2016.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; May 17, 2016.) © Kenny Diaz

Western Chat-Tanager, dorsal view. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic; April 15, 2018.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; March 9, 2017.) © Mitch Walters

Western Chat-Tanager. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; August 31, 2013.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; August 31, 2013.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager, singing and showing yellow crescent on lore. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic; December 14, 2012.) © Tony Pe

Western Chat-Tanager, puffed up during display, showing yellow crescents on lores. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic; December 14, 2012.) © Tony Pe

Western Chat-Tanager. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; March 9, 2017.) © Mitch Walters

Western Chat-Tanager. (Zapotén, Dominican Republic; February 16, 2016.) © Dušan M. Brinkhuizen

Western Chat-Tanager. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic; May 17, 2016.) © Dax M. Román E.

Western Chat-Tanager. (Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic; May 17, 2016.) © Dax M. Román E.

Cf. Eastern Chat-Tanager. Eastern and Western Chat-Tanagers occur within a few miles of each other in the Sierra de Bahoruco, but are not known to occur at any of the same sites. Western is about 15% longer, much more robust than Eastern, and has dark or plain gray orbital skin, whereas Eastern’s is bright yellow.

They also differ noticeably in posture and behavior: Western has the bearing of a thrush or thrasher, whereas Eastern often cocks its tail and twitches like a wren. Western’s vocalizations are slower and mellower than Eastern’s.

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of two recognized subspecies: tertius and abbotti (presumed extinct). Differences among populations of tertius suggest that it should regarded as two subspecies. These would be tertius of the Massif de la Hotte and selleanus of the Massif de la Selle and Sierra de Bahoruco.

Formerly considered conspecific with Eastern Chat-Tanager, together comprising the Chat Tanager, C. frugivorous.

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable.

Frontiers of Taxonomy: Haitian Chat-Tanagers.

Abbotti of Gonâve Island has not been reported in recent decades and is regarded as probably extinct. However, satellite photos appear to show that the island retains much of its native vegetation, so it seems possible that it may persist undetected. Recent recognition of the significant differences within Calyptophilus suggests the possibility that abbotti would qualify as a separate species, as its habitat must differ greatly from that of tertius.

The isolated Massif de la Hotte population is reportedly larger and darker, with more elaborate vocalizations. If so, then it would certainly rank at least as a separate subspecies, taking the name tertius and leaving the other known populations as selleanus—an old proposal that would be revived in this scenario.

References

Alas & Colores: Western Chat-Tanager (Calyptophilus tertius), https://alasycolores.com.do/en/aves/chirri-de-bahoruco.

Almonte, J.; Fernández, E. 2002. Eastern Calyptophilus frugivorus and Western Chat-tanagers C. tertius. Cotinga 17: 95-96.

BirdLife International. 2016. Calyptophilus tertius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22729082A104235769. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22729082A104235769.en. (Accessed June 2, 2019.)

eBird. 2019. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed June 2, 2019.)

Hilty, S. 2019. Western Chat-tanager (Calyptophilus tertius). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. http://www.hbw.com/node/61850. (Accessed June 2, 2019.)

Latta, S., C. Rimmer, A. Keith, J. Wiley, H. Raffaele, K. McFarland, and E. Fernandez. 2006. Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.