Birdfinding.info ⇒ Fairly common across much of its large range. Breeds and winters mainly in forests. During migration, it can be seen in large flocks at concentration points along the Great Lakes, in the Appalachians, and along the Gulf Coast of Texas and Veracruz, where daily counts in early October can reach into the hundreds of thousands.

Additional topics in Notes, below:

1. Broad-winged Hawk Migration Spectacle: Hawk-watching Sites.

2. Internal Taxonomy of Buteo platypterus.

3. Ongoing Colonization of the Lesser Antilles by Continental Broad-winged Hawks.

Broad-winged Hawk

Buteo platypterus

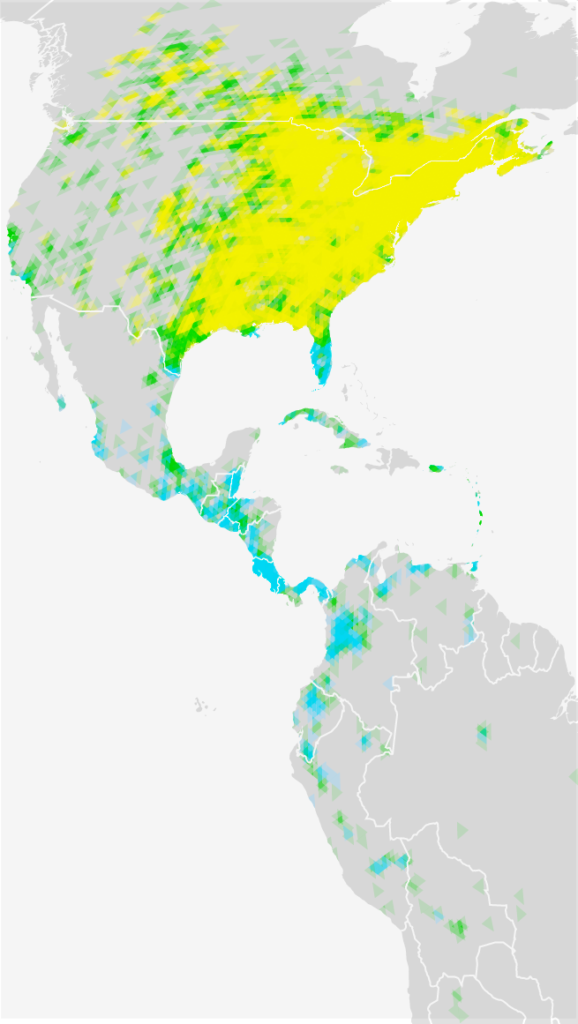

Breeds in central and eastern North America. Winters in Middle and South America. Resident populations in the West Indies.

Breeding. Deciduous and mixed forests across Canada from northeastern British Columbia and southwestern Northwest Territories east to Nova Scotia and south through the eastern U.S. to the Gulf Coast from eastern Texas to northern Florida. Uncommon west of Manitoba.

Nonbreeding. Winters in humid foothill and mountain forests from southwestern Mexico to Belize and southward through Central America and the Andes to central Bolivia, and east to the coastal ranges of Venezuela.

Small numbers winter irregularly in various areas outside the main wintering grounds: e.g., southern California, southern Baja California, peninsular Florida, Cuba, Trinidad, south in the Andes to northern Argentina, and locally across much of northern and central South America, including the Guianas, the Tepui region, and Amazonia.

Movements. Northbound and southbound movements are highly synchronized, as flocks form along travel corridors—most notably the Appalachians in late August and September—then concentrate in huge flocks that funnel through Middle America. The largest concentrations, numbering in the hundreds of thousands, gather in Veracruz, Mexico, in early to mid-October.

Much smaller numbers follow the Rockies, other western mountain ranges, and the Pacific Coast of North America.

In fall, stray flocks of juveniles sometimes follow the Florida coast southward and cross to Cuba. In spring, the inverse phenomenon has been observed in the southeastern Caribbean, as stray flocks apparently follow Venezuela’s Paria Peninsula to Trinidad, then continue north to Tobago and sometimes farther into the Lesser Antilles. (These occasional deviations evidently indicate the origins of the resident West Indian populations.)

West Indies. Resident in four disjunct areas of the West Indies: Cuba, Puerto Rico, Antigua, and the Lesser Antilles from Dominica to Tobago.

On Cuba, cubanensis is resident the length of the island, mainly in mountain forests and the Zapata Swamp area.

“Puerto Rican Broad-winged Hawk” (brunnescens) is rare and local, found mainly in the wet forest of the northwestern haystack hills around Río Abajo State Forest, and in smaller numbers in the Sierra de Luquillo and Sierra de Cayey.

Broad-winged Hawk Range Map Generated from eBird Basic Dataset 2015. © Imagesincommons

“Antiguan Broad-winged Hawk” (insulicola) occupies all terrestrial habitats on Antigua—not limited to forests.

In the Lesser Antilles, rivierei is resident on Dominica, Martinique, and St. Lucia, and antillarum is resident on St. Vincent, the larger Grenadines, Grenada, and Tobago—and possibly also becoming established as a breeding resident on Trinidad.

Identification

Highly variable and often indistinctly marked, but usually recognizable by a combination of size, shape, location, and habits. One of the smallest Buteos in length, but stocky and proportionately large-winged.

More readily identified in flight than at rest because its underwing and tail patterns are more consistent than its body plumage.

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus. (Río Blanco, Colombia; February 3, 2011.) © GYROLA2011

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus. (Punto Patiño, Darien, Panama; January 25, 2004.) © R.S. Scanlon

In Flight. Seen from below, the wings are mostly pale with blackish margins on the tips and trailing edge. Several other Buteos also show a dark border on the wings, but on Broad-winged the contrast between the dark border and otherwise pale underwings is distinctive. The tail is banded dark and light—appearing black and white in strong light, with a prominent broad black subterminal band, and narrower bands toward the base of the tail.

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterys. (Progreso Lakes, Texas; March 26, 2017.) © Dan Jones

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. antillarum. (Cuffie River Nature Retreat, Tobago; February 16, 2018.) © Robert Bochenek

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. rivierei, showing weakly contrasting borders on the wings. (Morne Diablotin National Park, Dominica; March 3, 2018.) © Brian Sullivan

The immature’s wings generally resemble adult’s—mostly pale with dark borders—but the the dark trailing edge is often narrow or indistinct.

The immature’s tail has a single prominent blackish subterminal band, and is otherwise finely barred.

(In the photos, also note the prominence of the immatures’ pale throat and the bold streaks and spots on the neck and breast.)

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, juvenile. (Hawk Hill, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Marin County, California; October 2, 2015.) © Paul Fenwick

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, juvenile. Tadoussac, Quebec; September 10, 2012.) © Samuel Denault

Adult Plumages. The underparts vary widely in color, tone, and pattern. Most individuals are distinctly darker on the chest.

Many show strong contrast between a mostly solid-colored chest and a much paler midsection and belly. Others are more evenly barred throughout the underparts, with a gradient from darker to paler—from denser to sparser barring.

The barring is usually rusty or medium-brown, but can also be sandy-brown, grayish, or chestnut.

A very rare black morph is essentially coal-black above and below. This variant is easily misidentifed as one of the Neotropical species, such as Zone-tailed or Short-tailed Hawks.

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, with strong contrast between mostly solid rusty chest and barred lower breast. (Biche, Trinidad; January 3, 2016) © Wendell S.J. Reyes

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, with medium-brown underparts. (Blanchisseuse Road, Trinidad; November 20, 2017.) © Jim Sweeney

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, with gray-brown underparts. (Hawkeye Wildlife Management Area; Iowa; April 26, 2013.) © Brandon Caswell

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, with pale, sparsely barred underparts. (Battle Creek Park, St. Paul, Minnesota; May 29, 2018.) © Bob Dunlap

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, with deep rufous underparts. (Paramin, Trinidad; December 8, 2013) © Feroze Omardeen

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, black morph. (Southwest Minnesota State University, Marshall, Minnesota; April 20, 2017.) © Garrett Wee

The upperparts are usually medium-brown, but vary from dark brown to pale brown. Dappled with large dark spots that are especially prominent on pale individuals.

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, with typical medium-brown upperparts. (Yarmouth, Nova Scotia; April 26, 2017.) © Alix d’Entremont

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, with pale-brown upperparts. (Johnson Sauk Trail State Park, Illinois; April 14, 2017.) © Stephen Hager

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, with gray-brown upperparts. (Rudement, Illinois; April 15, 2018.) © Cathy DeNeal

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. cubanensis, with pale upperparts and blackish spots. (Valle de Ancón, Pinar del Río, Cuba; March 20, 2015.) © Allan Hopkins

The West Indian subspecies generally fit within the range of variation that occurs on the continent, but the populations on each island tend to have predominant characteristics.

On Cuba, cubanensis typically has rusty underparts and bold barring on the flanks. This pattern is also common on the continent but seems more predominant on Cuba.

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. cubanensis. (Sendero Murmurios del Río, Pinar del Río, Cuba; December 23, 2017.) © Fabio Olmos

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. cubanensis. (Valle de Ancón, Pinar del Río, Cuba; March 20, 2015.) © Allan Hopkins

“Puerto Rican Broad-winged Hawk” (brunnescens) is the darkest subspecies. Its underparts are typically a mix of reddish brown and cream color—not white. The upper breast is mostly dark with a few pale spots. The lower breast and belly are evenly barred.

“Puerto Rican Broad-winged Hawk,” P. b. brunnescens, adult and nestling. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

“Puerto Rican Broad-winged Hawk,” P. b. brunnescens. El Yunque National Forest

“Antiguan Broad-winged Hawk” (insulicola) is the palest and smallest subspecies—about 10% smaller than the continental subspecies. Adults tend to retain markings typical of the immature plumages of other forms: spotted underparts and a distinct whisker streak.

It is Antigua’s only regularly occurring hawk, so identification is usually straightforward.

“Antiguan Broad-winged Hawk,” B. p. insulicola. (Sir Viv Richards Stadium, Antigua; May 15, 2011.) © Steve Ray

“Antiguan Broad-winged Hawk,” B. p. insulicola. (St. Paul, Antigua; August 16, 2013.) © Cesar Castillo

The Lesser Antillean subspecies (rivierei and antillarum) show a tendency to develop atypical plumages—apparently an artifact of historical inbreeding. These populations apparently receive occasional influxes of continental birds that mistakenly migrate north over the ocean from Venezuela or Trinidad, so it is unlikely that they have diverged significantly from the continental subspecies.

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. rivierei, an unusually rufous individual. (Syndicate, Dominica; December 21, 2016.) © Thomas Brooks

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. rivierei, an unusually dark-hooded individual. (Dauphin, St. Lucia; April 10, 2017.) © Frantz Delcroix

Broad-winged Hawk,” B. p. antillarum. (Kingstown, St. Vincent; January 29, 2018.) © Noam Markus

Immature Plumages. Immature Broad-winged Hawks are mostly dark brown above, usually with a paler head, pale eyebrow, and prominent dark whisker mark.

Unlike the adult, the upperside of the immature’s tail is mostly brown, with a single dark subterminal band and several indistinct narrow bands.

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, juvenile. (El Ávila National Park, Venezuela; December 2, 2017.) © Margareta Wieser

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. cubanensis, juvenile with an unusually pale head. (Playa Larga, Matanzas, Cuba; October 2010.) © Loïc Epelboin

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. rivierei, juvenile with unusually buffy underparts. (Prêcheur, Martinique; June 2007.) © Vincent Lemoine

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, juvenile, showing dark subterminal band on upperside of tail. (Cueva del Guacharo National Park, Monagas, Venezuela; January 9, 2012.) © Jay McGowan

The immature’s underparts are mostly whitish with bold blotches or streaks that are dense on the sides of the chest—and often on the midsection, forming a breastband (note the potential for confusion with Red-tailed Hawk). The throat is unmarked between the strong whisker marks, extending down to the center of the chest: a pale bib framed by bold streaks.

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, juvenile. (Cerli Bay, Trinidad; January 1, 2015.) © Nigel Lallsingh

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, juvenile. (Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba; September 13, 2016.) © France Desbiens

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. platypterus, juvenile. (Evergreen Cemetery, Fort Lauderdale, Florida; March 4, 2018.) © Meghan Pearson

Broad-winged Hawk, B. p. cubanensis, juvenile. (Soroa, Sierra del Rosario Biosphere Reserve, Artemisa, Cuba; March 23, 2017.) © R. Dennis Ringer

Cf. Immature Red-shouldered Hawk. Broad-winged and Red-shouldered Hawks overlap widely across much of their ranges and juveniles of the two species are easily confused with one another. In most cases, they are distinguishable based on differences in the patterns of streaks on the throat, neck, and chest.

Broad-winged: Immature typically has bold streaks that are densest from the whisker down along the sides of the neck to the sides of the chest, with a prominent pale, mostly unmarked area in between, from the throat to the center of the chest.

Red-shouldered: Immature typically has fine streaks that are fairly evenly distributed across the neck and chest. The density of the streaks varies. On heavily streaked individuals, the throat, neck, and chest are almost entirely dark.

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of six recognized subspecies, two of which are divergent, distinct forms: “Puerto Rican” (brunnescens) and “Antiguan” (insulicola). (See notes on internal taxonomy, below.)

Additional Topics Below:

1. Broad-winged Hawk Migration Spectacle: Hawk-watching Sites.

2. Internal Taxonomy of Buteo platypterus.

3. Ongoing Colonization of the Lesser Antilles by Continental Broad-winged Hawks.

1. Broad-winged Hawk Migration Spectacle: Hawk-watching Sites.

Hawk Cliff, Port Stanley, Ontario (mid-September)

Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, Pennsylvania (mid-September)

Smith Point, Chambers County, Texas

Hazel Bazemore County Park, Corpus Christi, Texas

Cardel, Veracruz (early October)

Panama Canal (mid-April)

2. Internal Taxonomy of Buteo platypterus.

The Clements checklist and some other authoritative sources recognize two distinct forms of Broad-winged Hawk, “Northern” and “Caribbean.” This classification must be incorrect as it appears to rely on an unstated assumption that the West Indian resident subspecies are relicts of a formerly pan-Caribbean distribution, but the evidence does not support this. Instead, the several West Indian resident subspecies (cubanensis on Cuba, brunnescens on Puerto Rico, insulicola on Antigua, rivierei on Dominica, Martinique, and St. Lucia, and antillarum from St. Vincent to Tobago) appear to represent multiple independent offshoots from the migratory continental stock, and therefore do not form a single taxonomic unit.

Considering the peculiar distribution of West Indian Broad-winged Hawk populations in relation to the migration patterns of the continental subspecies, it seems clear that each of the island populations likely had a unique, independent origin. In the west, Cuba is a natural backstop to catch lost southbound migrants, and in the east, the Lesser Antilles are well positioned to receive lost northbound migrants.

The islands that have resident populations are separated by large gaps, isolated from one another. Between Cuba and Puerto Rico lies the largest chunk of potential hawk habitat in the West Indies (i.e., Hispaniola), unoccupied. Puerto Rico and Antigua are separated by a large expanse of non-habitat: 200 miles of ocean with a few small scattered islands. Finally, between Antigua and Dominica, the apparently habitable island of Guadeloupe sits unoccupied.

Based on their locations and recorded observations, both the Cuban and Lesser Antillean populations likely continue to receive infusions of continental migrants. Southbound migrants reach Cuba annually, sometimes in large flocks. Conversely, flocks of northbound migrants are sometimes observed in the Lesser Antilles, principally on Tobago, but at least once on Dominica as well (see notes below on ongoing colonization of the Lesser Antilles).

In contrast, the “Puerto Rican” and “Antiguan” subspecies appear to be truly isolated—both from each other and from the other West Indian populations—and therefore have a much lower likelihood of contact and gene flow, providing the conditions for speciation. It is probably not coincidental that these two subspecies are also the most distinctive visually and ecologically. “Puerto Rican” is the darkest subspecies and occurs exclusively in rain forest. “Antiguan” is the palest, smallest, and least forest-associated subspecies.

To the extent that some degree of Caribbean speciation is recognized within Buteo platypterus, it appears to be significantly more advanced on Puerto Rico and Antigua than on Cuba and the Lesser Antilles. The evidence and reasonable inferences suggest that each island populations is its own phylogenetic branch, independently linked to the continental trunk, and that the more isolated Puerto Rican and Antiguan subspecies have each diverged more significantly than the less isolated Cuban and Lesser Antillean subspecies—so we recognize the “Puerto Rican” and “Antiguan” subspecies as distinct forms.

3. Ongoing Colonization of the Lesser Antilles by Continental Broad-winged Hawks.

There is evidence that the Lesser Antillean populations of Broad-winged Hawk are occasionally supplemented with northbound migrants from continental populations that follow Venezuela’s Paria Peninsula then cross to Trinidad and continue oversea, jumping from island to island. Migrating flocks have been observed at both ends of the Broadwing’s Lesser Antillean range, on Tobago and Dominica.

Gus van Vliet writes on eBird (https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S26387181) regarding a sighting from April 6, 1975:

“Without a doubt, the most unusual sighting that I made during my 5-month stay in Dominica. I observed a kettle of 125-150 BWHA soaring at mid-day above the Hampstead River valley rainforest. Clearly, these birds were migrants and not residents. The birds were identified by their size and tail pattern, eliminating potential Swainson’s Hawks. As far as I know, at the time of this observation there was no hint of BWHA migration through the Lesser Antilles. However, subsequent comparable spring sightings of 100’s of BWHA’s have been observed from southwest Tobago (~500 km south of Dominica) by Martyn Kenefick during 23-24 March 2001: (http://ebird.org/ebird/view/checklist/S18771414; http://ebird.org/ebird/view/checklist/S18771433) and then again seven years later on 22 March 2008 (http://ebird.org/ebird/view/checklist/S18783526).”

These disoriented migrants were unlikely to reach their North American breeding grounds and presumably illustrate the origin of the Lesser Antillean resident populations. Its habit of migrating in large flocks suits the Broad-winged Hawk to episodic colonization of new outposts. It seems probable that some of these disoriented birds remain and join the local resident populations.

References

Ascanio, D., G.A. Rodriguez, and R. Restall. 2017. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

eBird. 2018. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed September 29, 2018.)

Ferguson-Lees, J., and D.A. Christie. 2001. Raptors of the World. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston.

ffrench, R. 2012. A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago (Third Edition). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Garrido, O.H., and A. Kirkconnell. 2000. Field Guide to the Birds of Cuba. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Global Raptor Information Network. 2018. Species account: Broad-winged Hawk: Buteo platypterus. http://www.globalraptors.org. (Posted January 12, 2011; accessed September 29, 2018.)

Latta, S., C. Rimmer, A. Keith, J. Wiley, H. Raffaele, K. McFarland, and E. Fernandez. 2006. Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Lindsay, K.C., and J. Bacle. 2010. Ecological Characterization of the Body Ponds Watershed (report to Environmental Tourism Consulting). http://www.irf.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/EcologicalCharacterizationBodyPondsWatershedAntigua_Lindsay_2010.pdf.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y.

Ridgely, R.S., and J.A. Gwynne. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Panama (Second Edition). Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Riesing, M.J., L. Kruckenhauser, A. Gamauf, and E. Haring. 2003. Molecular phylogeny of the genus Buteo (Aves: Accipitridae) based on mitochondrial marker sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 27:328-342.

Riley, J.H. 1908. Notes on the Broad-winged Hawks of the West Indies, with Description of a New Form. Auk 25:268-276.

Rowlett, R.A. 1980. Migrant Broad-winged Hawks in Tobago. Journal of the Hawk Migration Association of North America 2:54.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1997. Puerto Rican Broad-winged Hawk and Puerto Rican Sharp-shinned Hawk (Buteo platypterus brunnescens and Accipiter striatus venator) Recovery Plan. https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/970908.pdf.

Vilella, F.J. and D.W. Hengstenberg. 2006. Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo platypterus brunnescens) movements and habitat use in a moist limestone forest of Puerto Rico. Ornitología Neotropical 17: 563-579.

White, C.M., P. Boesman, and J.S. Marks. 2018. Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo platypterus). In Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D.A. Christie, and E. de Juana, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. https://www.hbw.com/node/53124. (Accessed September 29, 2018.)

Wikiaves, Gavião-de-asa-larga, https://www.wikiaves.com.br/gaviao-de-asa-larga.